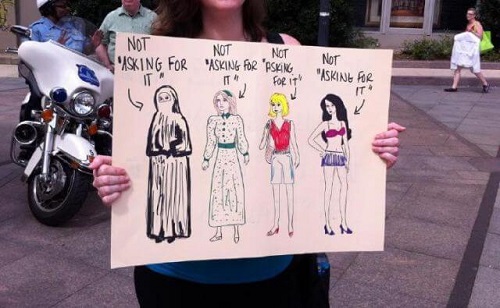

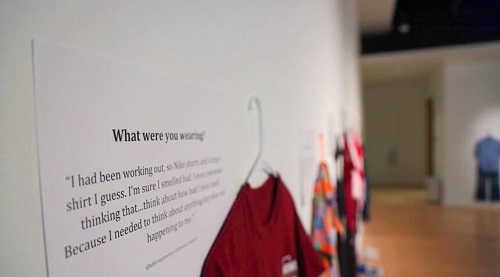

After all these years and many criticisms against the movement on the basis of being too white, too heterosexual, and too rich, in other words on the basis of its lack of an intersectional approach, Burke revisits her roots as a youth worker working with Black children and women of color, reflects on the current status of the movement, and speculates about its future. According to Burke, a survivor of sexual abuse herself, while ‘Harvey Weinstein is a symbolic case and to see a high profile, rich white man be convicted of a crime, in general, is always astonishing’, ‘celebrity goes to jail or not, is not sustainable as a movement’, highlighting this way both the classism of movement and the lack of an understanding of sexual abuse as a systemic problem endemic to a heteropatriarchal society beyond the celebrification of a handful of viral and ‘high profile’ cases. And she continues: ‘What we need to be talking about is the everyday woman, man, trans person, child, and disabled person. All the people who are not rich, white, and famous, who deal with sexual violence on everyday basis. We need to talk about the systems that are still in place that allow that to happen.’ In other words, not only is the movement far from over, but in a self-reflective gesture a need for an intersectional, systemic, and from the below approach is a necessary one in order to fulfill its political and social promise. There is a lot of work to be done, and the alarming statistics on this matter testify to the lethal combination of invisibility and pervasiveness of sexual violence in the USA.

Login

Login