In our latest article, we discussed the interlocking issues of postcoloniality and colonial feminism as we took our cue from Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old Kurdish woman who was arrested and murdered by the Guidance or Morality patrol in Tehran on 13 September 2022. Tracing the history of Iran, it became clear that the current protests for women’s rights and against the compulsory hijab are not the first of their kind in the country, but rather a part of a complicated and longstanding genealogy of the wider and intersectional Iranian Democracy Movement that has been at the heart of the abovementioned Iranian protects. On top of that, the war against women in Iran is not a recent phenomenon, but rather one deeply rooted in the recent history of the country with references to both political regimes and religious reforms at least since the late 70s, that is since the Iranian or Islamic Revolution.

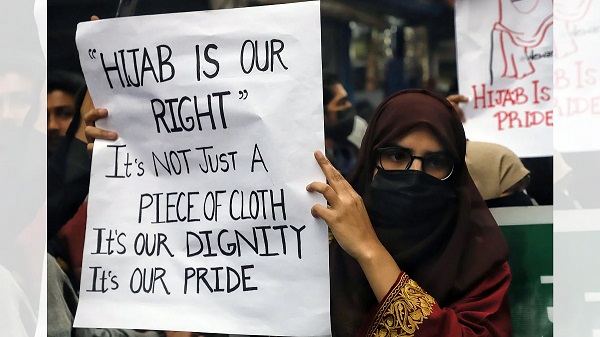

The unjust and sexist killing of Mahsa was indisputably the spark that set fire to the patriarchal institutions in Iran thanks to the widespread protests across the country, a revolutionary surge that put under question well-cherished social, political, and religious beliefs, but it was also another ‘oriental spectacle’ for the western media that have covered Mahsa’s story and the generalized civil unrest over the past few months. This orientalist media coverage of these events was the main subject matter of our second article dedicated to this issue. This incessant flow of news that has fuelled our smartphones, laptops, or TV screens revolves around a particular piece of cloth, the veil, and in this particular case, the hijab.

Login

Login