Even nowadays, there seems to be a veil of silence and invisibility surrounded HIV/AIDS especially in its relation to male homosexuality in the case of Greece: HIV/AIDS-related issues are rarely part of the daily political agenda of both the grass-root activist groups and the more ‘institutionalized’ gay rights NGOs, the issue is understudied by social sciences and undernarrativized only by a handful of literary and cinematic texts (Paparousi, 2012; Kyriakos, 2016), never part of the political sphere nor of the LBGT counterpublics, lives without testimony and ungrievable deaths (Yannakopoulos, 2011), an ‘aphasic’ non-place ‘of concealment and of denial of the political’ (Papanikolaou, 2018). All these reasons make the work of Positive Voice even more invaluable as they aim at securing better prevention and counselling practices, healthcare services, and social care to seropositive persons and groups vulnerable to HIV. Also, they work towards social acceptance, solidarity, and support of the abovementioned groups in order to tackle violations of their human dignity and rights.

Learn here how each purchase helps us support Positive Voice’s work with HIV/AIDS in Greece in the context of our CSR program!

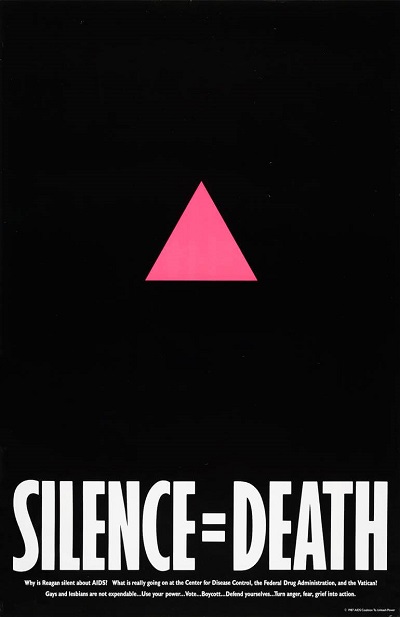

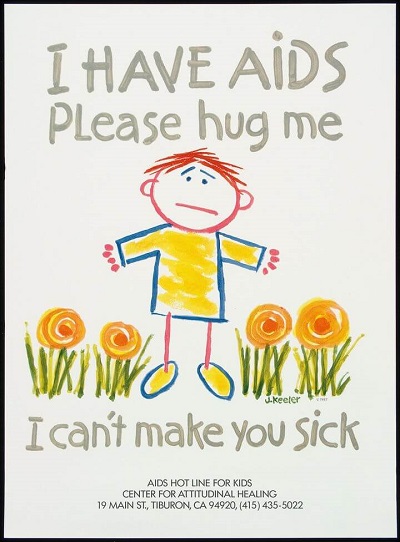

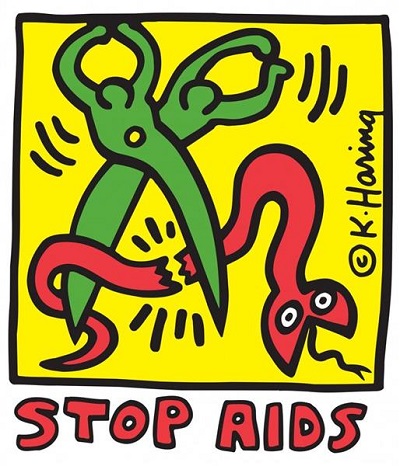

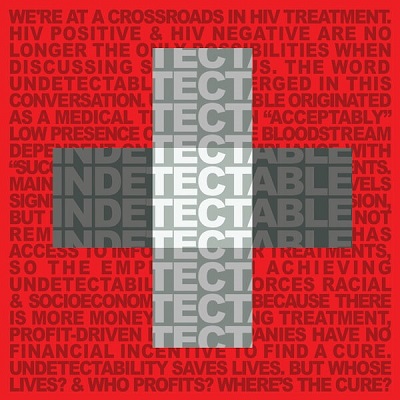

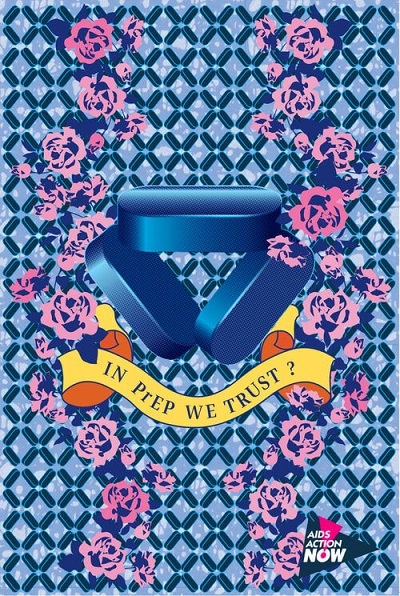

*The images present iconic AIDS Activist Artworks, part of what is also known as HIV art.

Login

Login