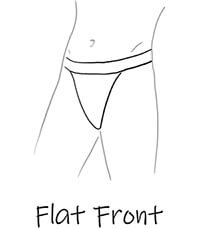

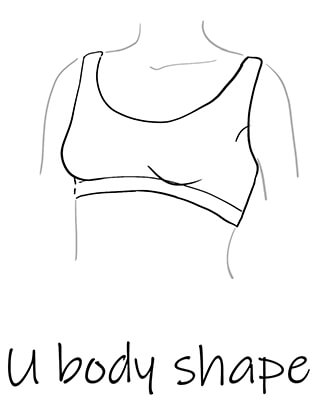

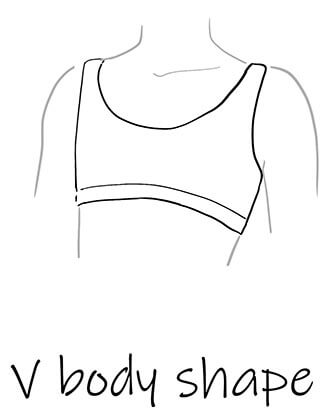

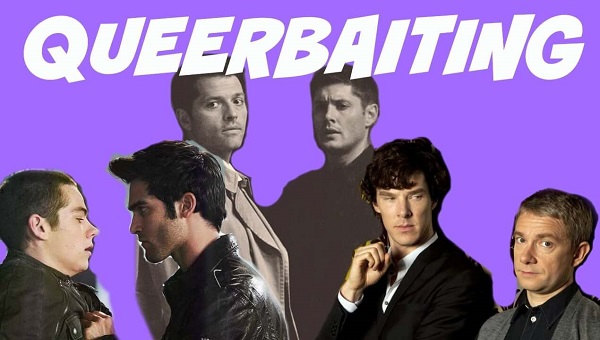

Unfortunately, queerbaiting is as pervasive as queerphobia itself and it could be in fact a far more insidious form of queerphobia than -let’s say- explicit hate speech. It works in a way that crawls under viewers' skin and makes them question their own reading of the film despite the carefully planted cues all over the narrative. In a way, queerbaiting follows the logic of gaslighting, a form of emotional abuse and manipulation when someone makes you question your own beliefs and perception of reality and which leaves you with a deep sense of frustration. In the case of queerbaiting, this invalidation of own’s sexual identity is many times part and parcel of queer capitalism itself. Here, the difference that the sexual or gender identity is gets gentrified as another formal fungible difference that lacks content. The multiple axes of oppression such as race and able-bodiedness among others are treated like boxes on a checklist in order to make sure that the final cultural product is ‘diverse’ enough to attract a wider audience base. When it comes to the market part of which Ecce Homo as a queer non-binary, body-positive, and slow-fashion underwear brand is, the vast majority of gay male underwear brands are deploying queerbaiting as their main marketing strategy. On their e-shops, any word or depiction that would signify queerness, and gayness in specific, is effaced, and instead, the catalog photographs are queer coded resorting to hyper-masculinist tropes in order to be perceived by the gay male consumer as queer yet in a very limited sense. As a result, oversexualized and hegemonic visual representations of masculinity are used as bait for queer consumers while at the same time attempting to avoid alienating heterosexual ones.

References:

- Fathallah J (2015) Moriarty’s ghost: or the queer disruption of the BBC’s Sherlock

- Nordin E (2015) From Queer Reading to Queerbaiting: The Battle over the Polysemic Text and the Power of Hermeneutics

Login

Login