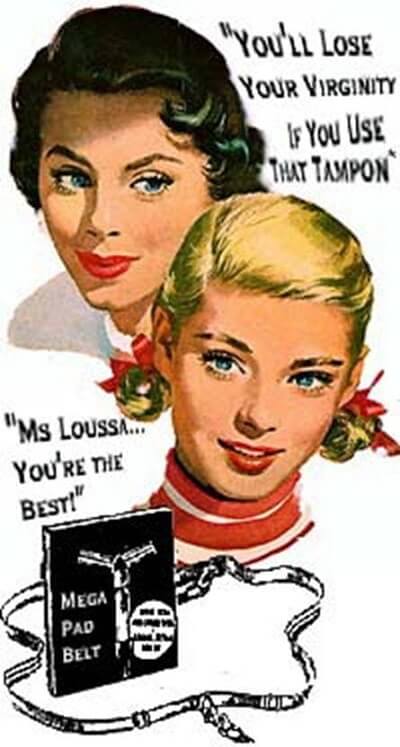

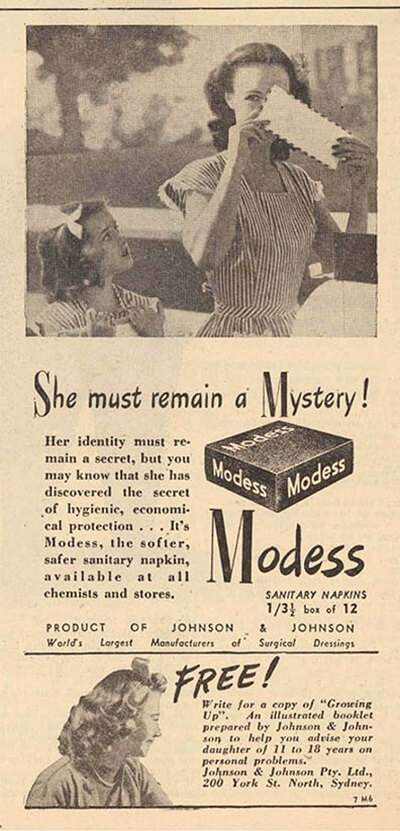

According to the dominant heterosexist ideology that has its roots in the history of the medical imaginary of ‘the West’ that still resonates today despite the advances in biomedicine, the male anatomy, whatever that means, constitutes the paradigmatic human form, the prototype for all human bodies. In contrast, the female body is considered to be a non-male one, a body that is described and assigned meanings and value to only in comparison to the male one. As a result, the female body with its orifices, the pregnancy, and the monthly period has been and continues to be conceptualized as inferior, lacking, porous and uncontrollable. Since the body has always been treated as a threshold between the psychical, the bodily and the social, these traits of the female body have been transposed to a series of naturalized assumptions about the female psyche and the social roles that women play. If men according to their anatomy are self-contained and self-mastered creatures that are in control of their bodily fluids and in possession of a powerful phallus that makes them perfect for rational reasoning and public duties, women -on the other hand- due to their porous and leaky anatomy and lacking a phallus are considered to be emotional creatures unable to control their bodily fluids and with undefined bodily limits that condemns them to the private realm of a household. When it comes to period, let us remember that it has been strategically understood by men as a failure of the human body and soul, a sign of uncontrollable and irrational emotional turmoil during ‘that time of the month’, a biologically based excuse for the disfranchisement of women during the women’s suffrage movement in the 19th and 20th century, their decades-long fight to win the right to vote.

Login

Login