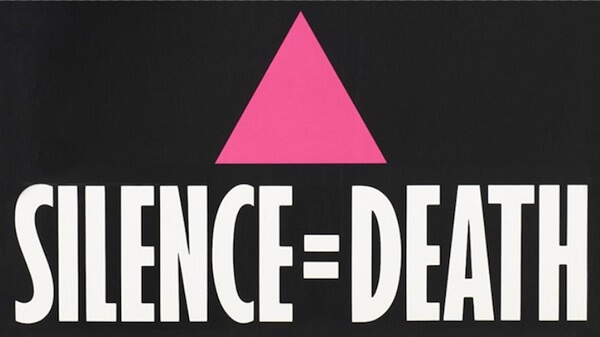

Since the 2005 United Nations General Assembly resolution 60/7, the 27th of each January marks the International Holocaust Remembrance Day or the International Day in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust, an international Memorial Day that commemorates the victims of the Holocaust, that is not only the Jewish people who faced the ‘final solution’ to the ‘Jewish question’ they posed to the ‘purity’ and ‘superiority’ of the Aryan race but also the hundreds of other persons belonging to minority groups that were imprisoned in concentration camps and/or killed between 1933 and 1945 by Nazi Germany, among them Jehovah's Witnesses, Roma, Afro-Germans, homosexuals, people with disabilities, etc. This date is far from accidental as it was on 27 January 1945 when the Auschwitz concentration camp was liberated by the Red Army marking the end of World War II. According to Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon’s statement for the observance of the Holocaust Victims Memorial Day in 2008, ‘the International Day in memory of the victims of the Holocaust is thus a day on which we must reassert our commitment to human rights,’ while at the same time, he urges us to ‘go beyond remembrance, and make sure that new generations know this history.’

Along with the foundation of respective national remembrance days, memorials, and monuments in many countries around the world, we have witnessed over the last decades the attempts of these minority groups to reclaim their history and their right to memory and memorialization engaging in a feverish mnemopolitics as a core part of their own identity and history. If ‘we must apply the lessons of the Holocaust to today’s world’ as Ki-Moon’s inspirational words read, then we must recognize that the history of the Holocaust continues to be after all these decades an unfinished archive open to interpretations and reappropriations on both sides on the history, an ever-replenished archive not only of events and official documents, but of feelings, thoughts, memories, and oral narratives as well. This archive fever keeps the history, the violence, and the injustices alive as it allows the past to haunt the present, a ghostly presence and reminder that Nazism which gave rise to and justified such atrocities is far from over but rather many of its ideological components permeate our current predicament on a planetary level.

Login

Login