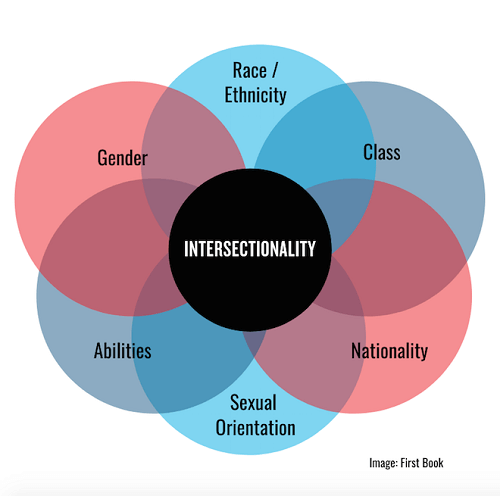

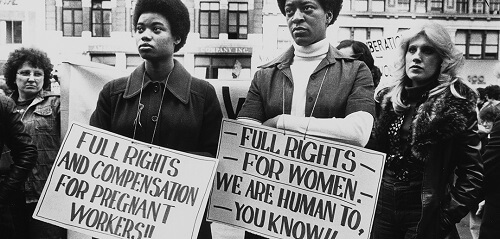

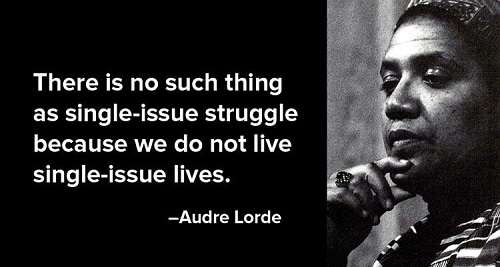

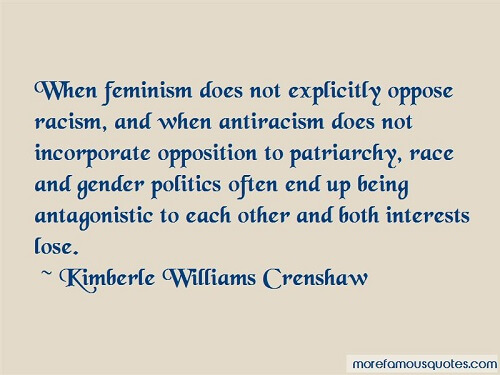

In this context, underwear is both like a second skin, the most personal and invisible piece of clothing, and the first line of defense against the world. It is both a way of expressing and communicating our gender, sexuality, race, etc., and the site where gender and sexual norms or racial expectations of what matters as a body are violently inscribed to like a tattoo. Underwear is both that which gives a body its shape and meaning by ‘fashioning’ it according to certain heteronormative, racial, able-bodied, and class -among others- criteria, and it is also a small piece of fabric that is strategically mis-used by the bodies that fall outside these normative boxes in order to become subversive or even subversively sexy, a living political statement of defiance full of passion.

Login

Login