We have come a long way in discussing the issue of color over the course of Ecce Homo’s blog! This article at hand completes our series on the immense symbolic, psychological, social, and financial importance color holds for the fashion industry and culture in general. In the first blog post of the series titled ‘Why does color matter?’, we delineate the valuable insights one can gain from taking a closer look at the various uses and meanings of colors across time and space. One such insight is that thinking in colors is inevitably thinking in terms of gender and sexuality, and the history of sex-specific colors reveals the culturally specific and historical contingent ‘nature’ of the gender-coding of colors, and of gender and sexuality itself. Taking the yearly announcement of the Color of the Year by the Pantone Color Institute as an example helped us dig deeper into the financial stakes of color within the fashion industry. More importantly, we have come to realize that, even though at first glance the choice of a specific color seems to be an expression of our personal style, a highly individualizing gesture aiming at setting us apart from the crowds, the decision of these very colors we ‘freely’ pick ultimately belongs to a handful of color experts, marketing strategists, and fashion designers.

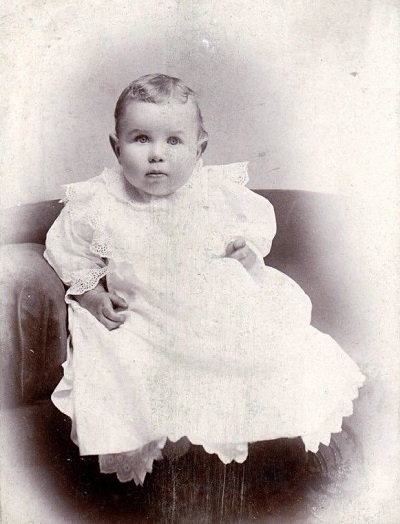

This lead us to our second blog post under the title ‘The color of gender’ in the context of which we focused on the powerful grid of symbolic associations in which each color acquires its meaning as they come to signify a certain attitude, an affect, a thought, a worldview, or a lifestyle. The ‘pink for girls, blue for boys’ styling rule was offered as a case study on the psychology of colors with each of these two signifying visually a series of antithetical yet complementary cognitive abilities and emotional capacities unequally distributed along the lines of a strict gender binary. In what follows, we are going to tackle this baby fashion norm from a historical perspective. How has this norm come to be in the first place? Has there always been a norm regarding baby clothing to begin with?

Login

Login