Regarding the first point, the ethics, both male homoerotic desire and HIV/AIDS are perceived as transgressions of the gendered and sexual order by exposing its ‘polymorphously perverse’ underside and resulting in the formation of stigmatized and spoiled identities based on processes of othering that construct both PLWHA and male homosexuals as morally corrupt while at the same time naturalize the symbolic link between them via a series of metaphors. This cultural logic works in tandem with the aforementioned mentality of ‘natural male sexuality’ that conceptualizes the ‘poustis’ as a type of person ‘who fundamentally lacks full humanity and his moral weakness exposes him to all sorts of evil dispositions’, according to Loizos and Papataxiarchis, and the ethnomedical ‘theories’ of disease aetiology that consider any biological disease to be the result of a sin, both of them imagined as ‘an intrusion of evil spirits that penetrate the body and render the person ill’, according to Plexoussaki and Yannakopoulos.

In other words, HIV/AIDS appears to be the punishment for the ‘immorality of the poustia…of the soul’, Yannakopoulos puts it, and it is in this context that Plexoussaki and Yannakopoulos describe a series of mechanisms of production of social difference in the 90s in Greece, in this cases the doubly marked identities of PLWA, like the intensive questioning regarding the ‘shady’ and immoral, as presumed by the doctors, ‘medical’ past of the patients, the corporeal practices of protection employed by the medical staff in their everyday contact with the patients and the construction of the patient’s ward at the hospital as a ‘dangerous’ place.

Stay tuned as we are going to delve deeper both into the ways AIDS patients were treated in the 90s in Greece and the political-activist response by the Greek LGBTIQA+ movement to this pandemic.

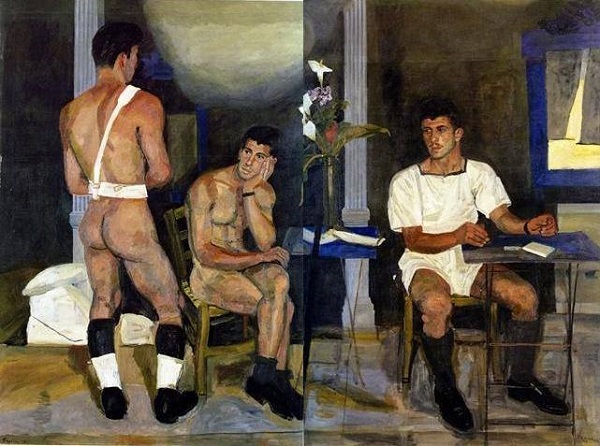

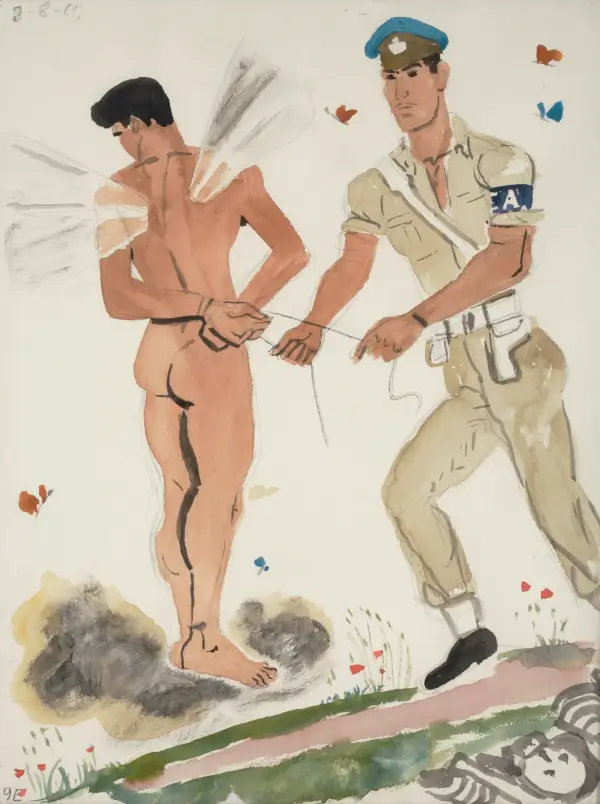

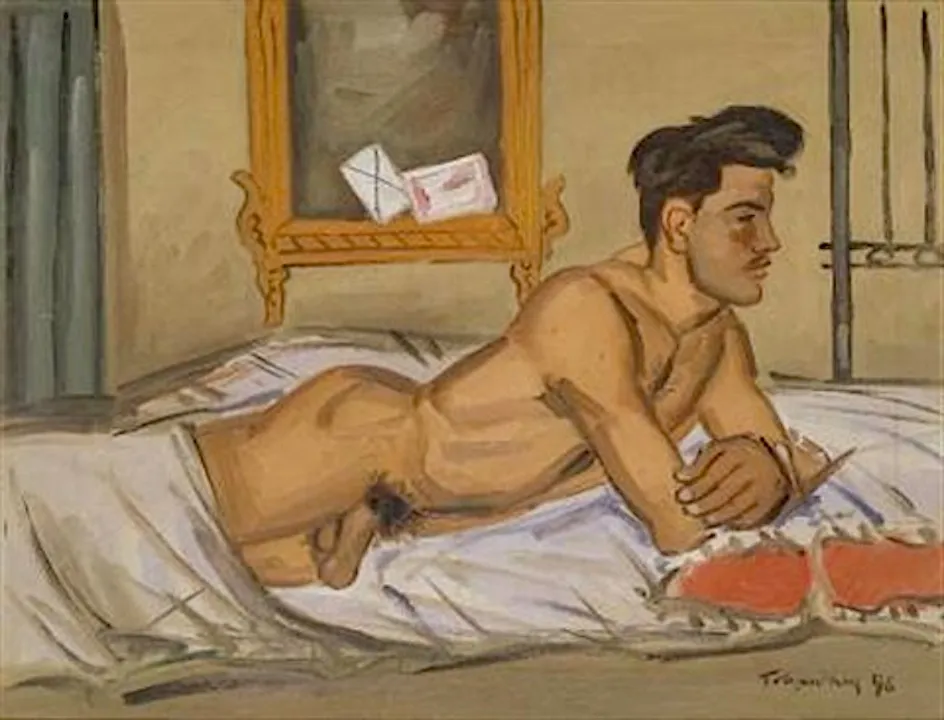

* The paintings presented here are by Yannis Tsarouchis, the gay Greek artist-provocateur, whose mid-20th century works of art explored homoeroticism.

Login

Login