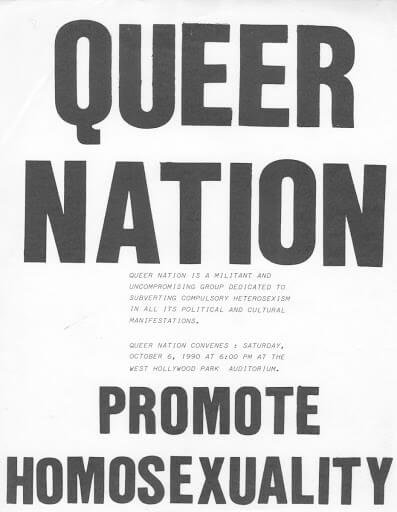

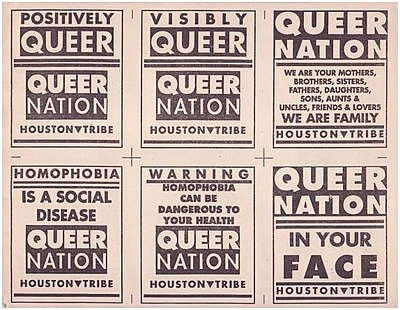

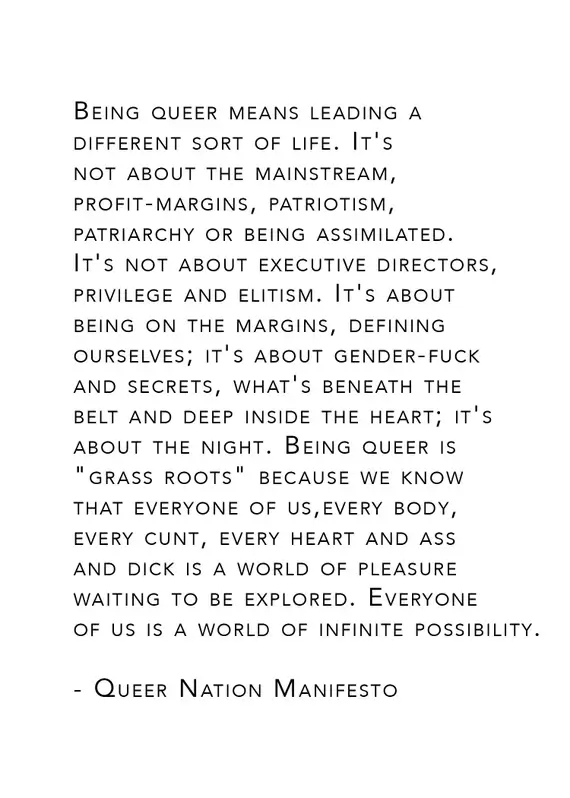

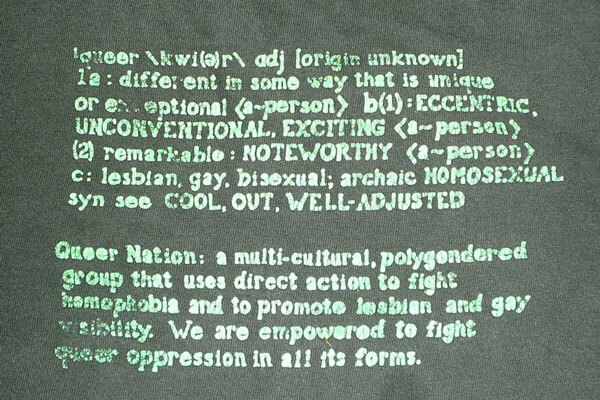

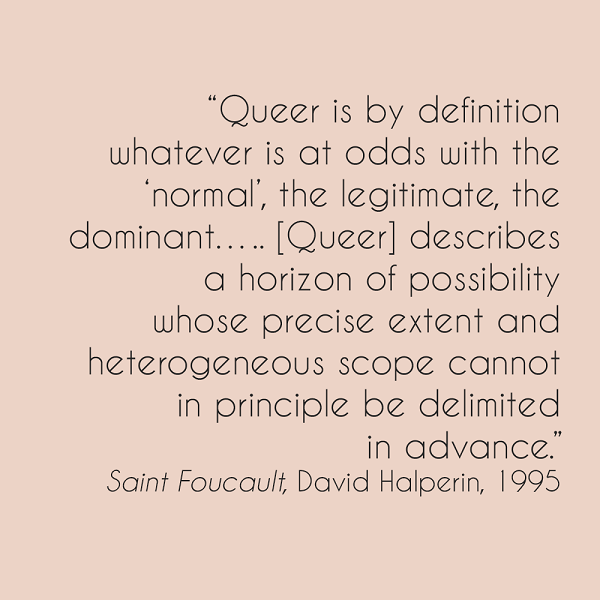

Having said that, it seems contradictive -to say the least- the inclusion of queer as an identity in the LGBTIQA+ acronym. The manifesto of Queer Nation, one of the first queer groups of that time, is a good starting point for understanding what queer is all about. Queer is constitutively anti-identitarian, a political attitude of direct action beyond lobbyism and rights discourse, a personal aesthetic of fluid and dynamic becoming that is irreducible to sexual identities such as gay or lesbian. Queer names anything that goes against the regime of normal. Queer defies the traditional understanding of politics. Queer is a grassroots coalitional politics. Queer resists a definitional closure and remains in a constant flux of becoming with others. Ironically, queer comes closer to the other term with which is interchangeable in the acronym, the questioning. Queer is a questioning of politics, of definitions, of power, of identities. Queer detests all the mantras of identity politics, such as inclusion and visibility, because it resists assimilation to both heteronormative and homonormative ways of longing and belonging. Queer takes identity to be the insidious psychic life of power that grants visibility only to be disciplined by it, the master’s tool that will never dismantle the master’s house. By reducing queer to another identity, one erases its rich history and political specificity. But is it possible to live without an identity? Is an identity all that bad after all? Can anyone afford this anti-identitarian embrace of queerness? And finally, has queer kept its promise after all those years? Maybe, queer has inevitably become another identity, a new normal?

Login

Login