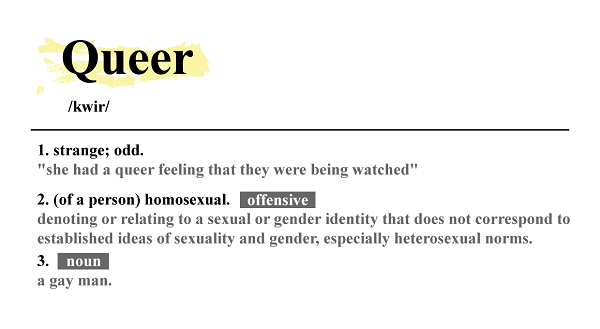

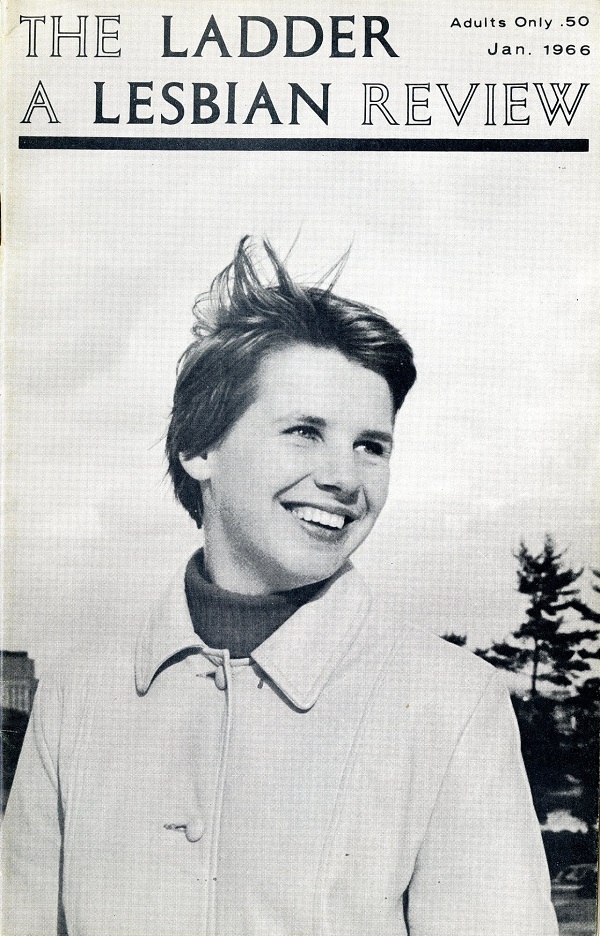

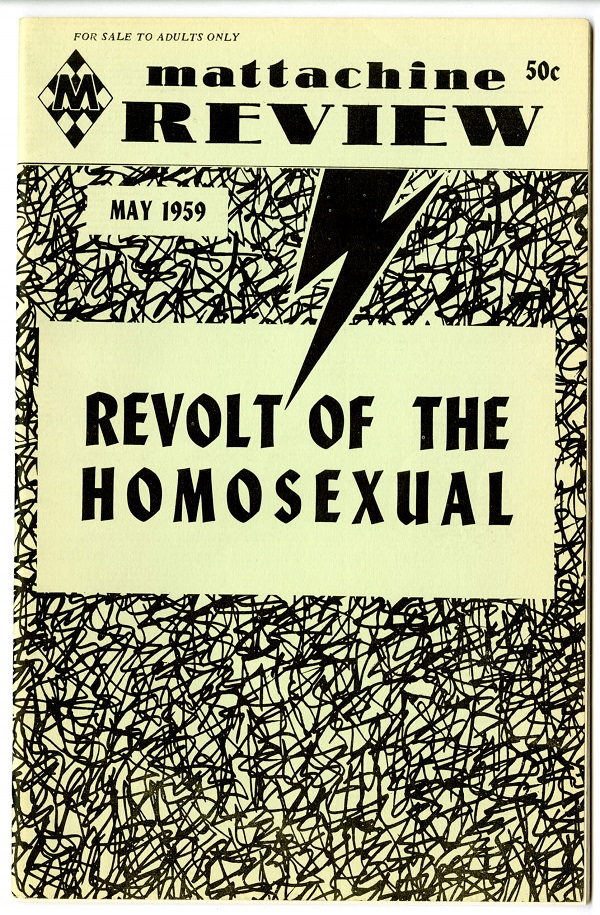

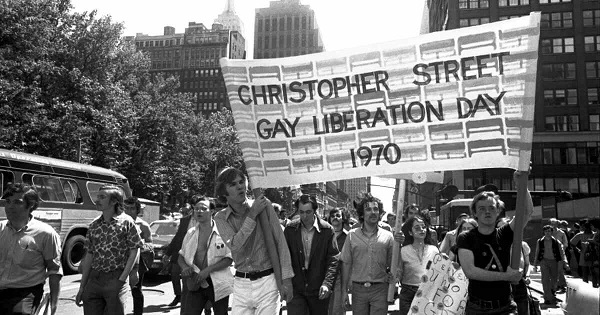

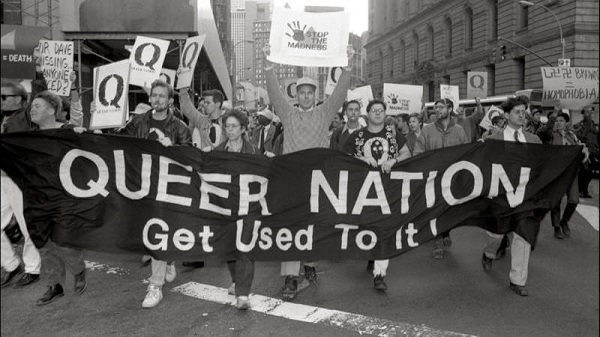

From the 40s up to the mid-80s, it seems that the word queer was perceived mainly as an injurious term evoked to stigmatize homosexuals, and as such it was not a political signified with which any gay man or woman would have identified. However, all this changed with the rise of queer activism and theory. In the mid-80s, gay activists and scholars re-appropriated the up to this point derogatory term queer and passionately identified with it and with the political vision it animated. A series of political, financial, and societal conditions of this turbulent period made obvious the inefficacy of the Gay Rights Movement as the latter took a homonormative turn towards assimilation and conservatism. Embracing the negative associations of the term queer, queerness became a new political signifier in the spirit of pride and defiance. Among the first grassroots organizations that used the word queer as a positive self-label was the Queer Nation founded in the early 90s, an offshoot of ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. Here, the meaning of queer has changed and significantly expanded beyond the identity of gayness. The co-optation of the term from an offensive term and site of trauma to a badge of pride far exceeds the limits of its linguistic use. This semantic change signaled a new way of thinking about homosexuality and politics itself generating new conceptualizations of gender and sexuality and giving birth to radical forms of political protest and action.

This was the first of a series of articles dedicated to queerness. Stay tuned as we will delve deeper into the history and politics of queerness in our following posts!

References:

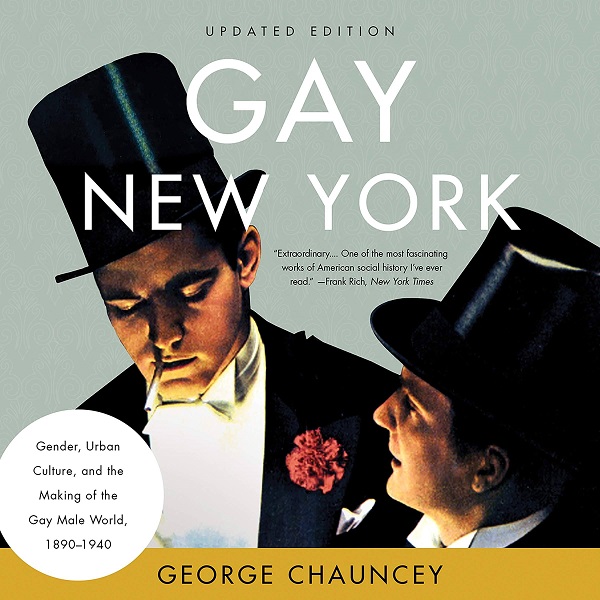

Gay New York (1994), by George Chancey

Tendencies (1993), by Eve Sedgwick

Queer(y)ing the “Modern Homosexual” (2012), by Jeffrey Weeks

Login

Login