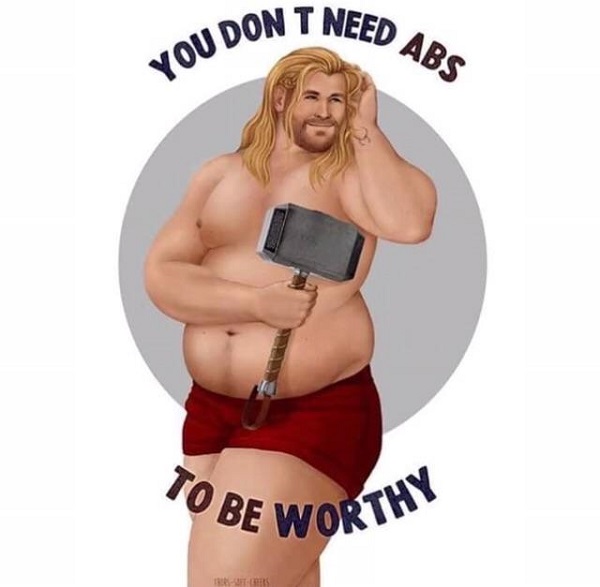

Many times, during the course of this blog, we have touched upon the issue of body positivity as it lies deep at the heart of our corporate identity, our aesthetic vision, and our political commitments. For example, our ‘Body positivity and queer fashion’ blog post was our first attempt to navigate the uneasy relationship between these two as a start-up queer brand that was trying to find its own footing in the complex and ever-changing landscape of the worldwide fashion industry. After all, Ecce Homo identifies as a queer-feminist non-binary, slow-fashion, and body-positive underwear brand since its inception a few years back, and both our designs and our extensive Corporate Social Responsibility program are living proof of our commitment to these guiding principles. Admittedly, since this very first article, a lot has changed: the proliferation of appearance-centered social media platforms, the intensification of their presence in our Covid and post-Covid highly digitalized lives, the increased cultural impact of the visual representations they put forward and disseminate worldwide, the rise of the #MeToo and the raising of a new feminist consciousness, to name but a few.

In addition, we, Ecce Homo, have come a long way since 2020: we have designed and manufactured six successful underwear collections, our social media engagement has exponentially grown, we have released many advertising campaigns completely in-house curated, our CSR program has significantly expanded and, as we speak, it supports six LGBTIAQ+ organizations in Greece, Europe, and the USA. One could say that our first and foremost preoccupation across all these diverse areas has been the promotion of body positivity in the widest, most inclusive, and most intersectional sense possible. Back then, in 2020, we wrote: ‘Ecce Homo dares to differ from its competitors in the queer underwear market. We aspire to provide our customers with clothes that do not reproduce uncritically the hegemonic representations of what counts as ‘beautiful’, a seemingly innocent adjective which, nevertheless, hides and further consolidates discriminatory behaviors and prejudices among the members of the queer community on the basis of their gender and sexual identity, age, ethnicity, race, able-bodiedness, and embodiment.’ We still work by these words.

Login

Login