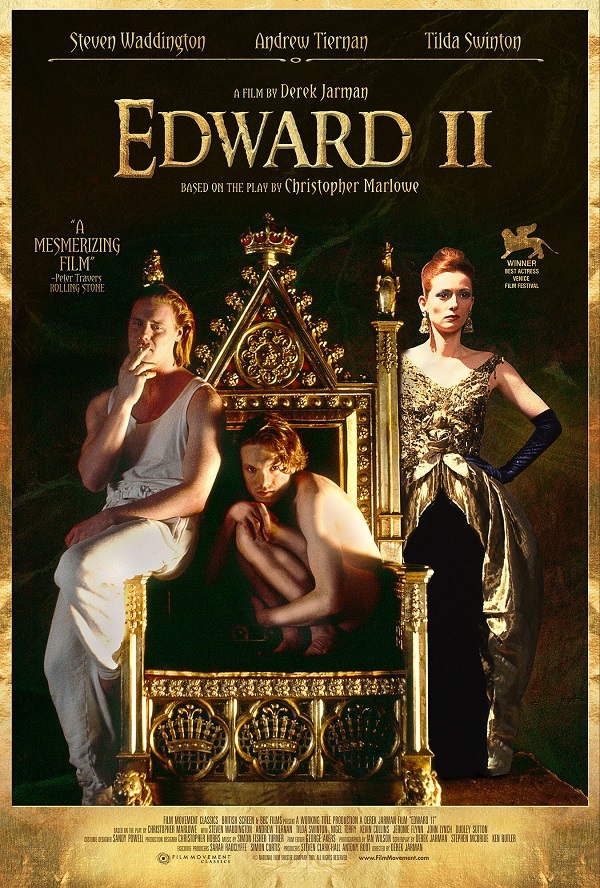

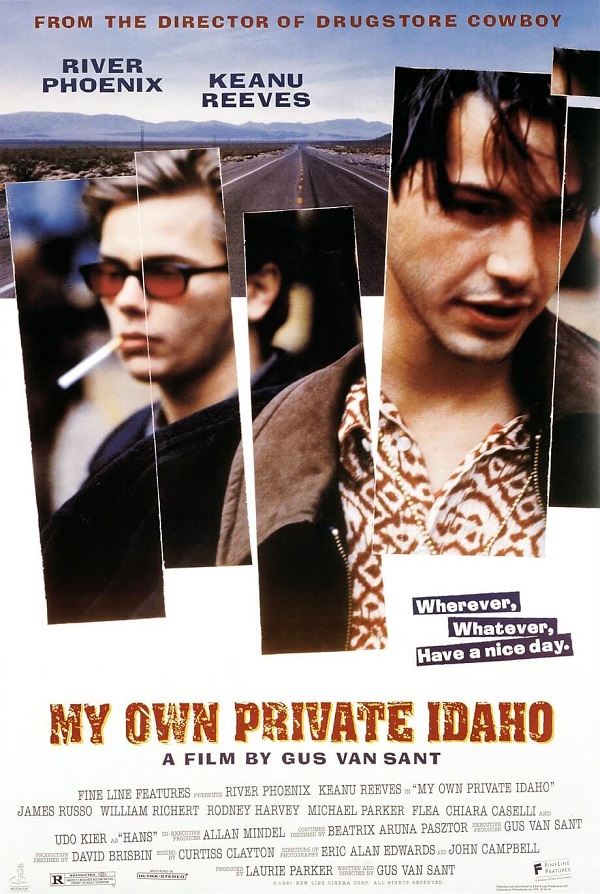

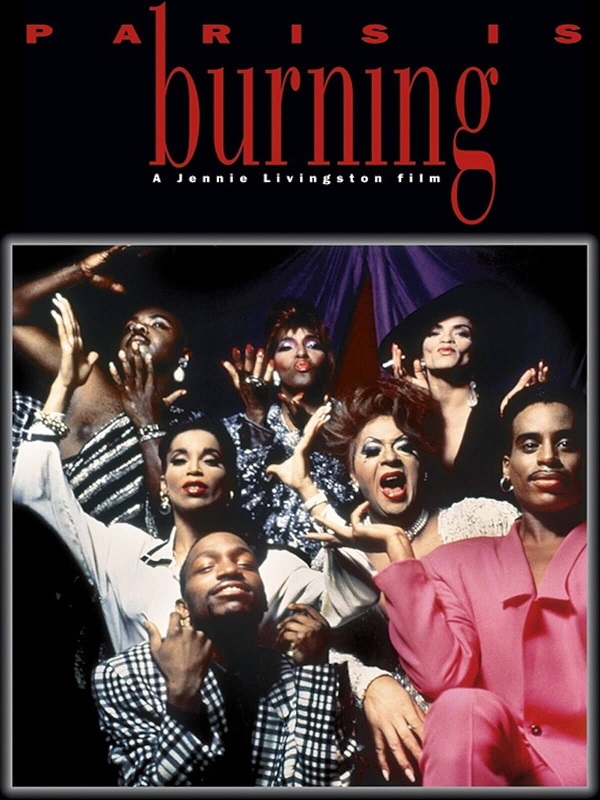

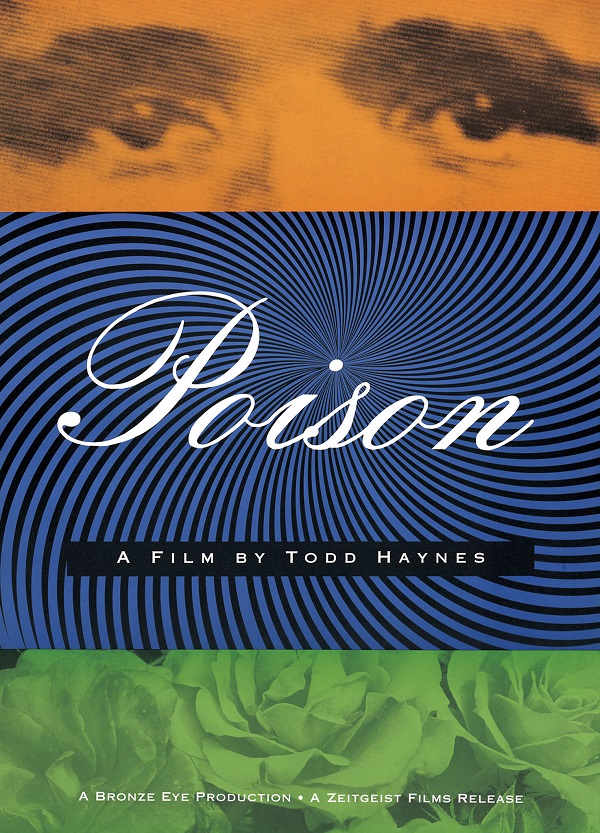

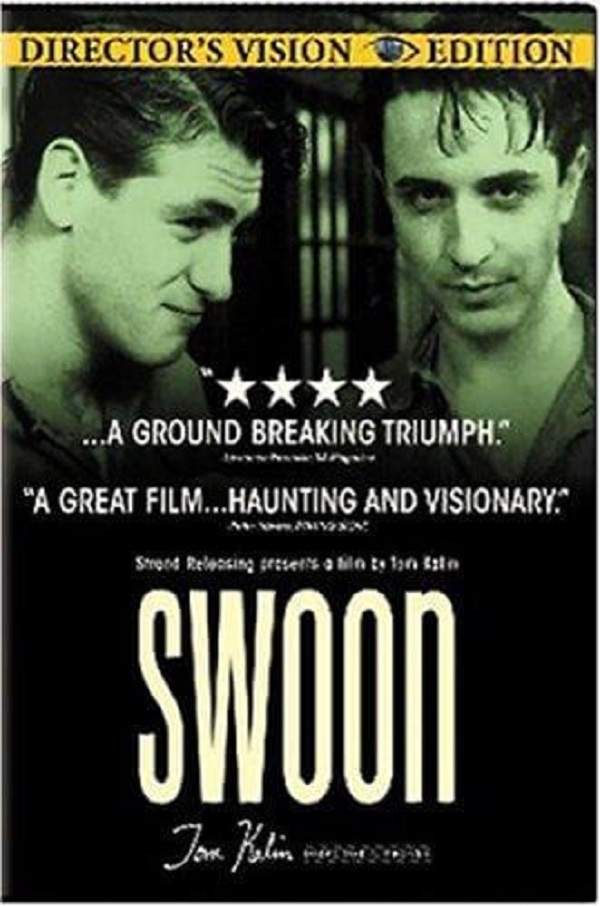

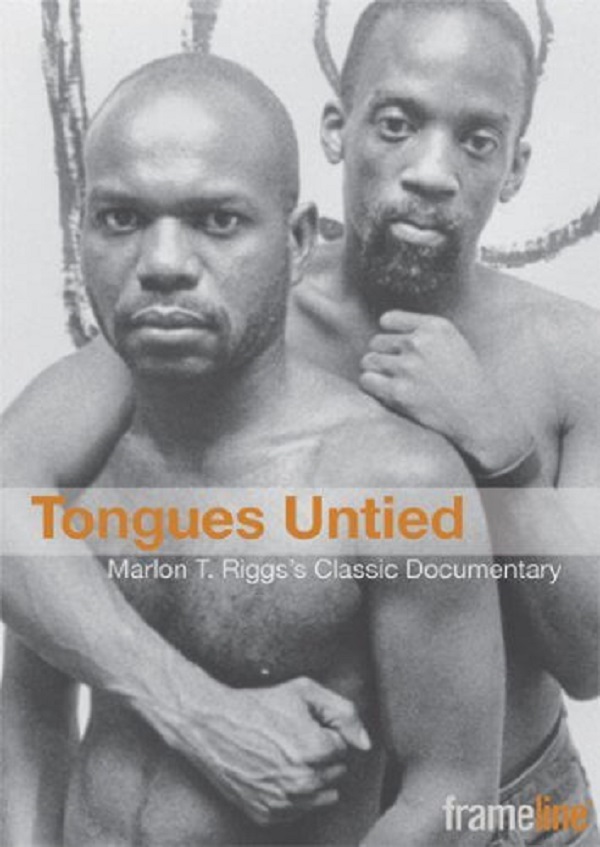

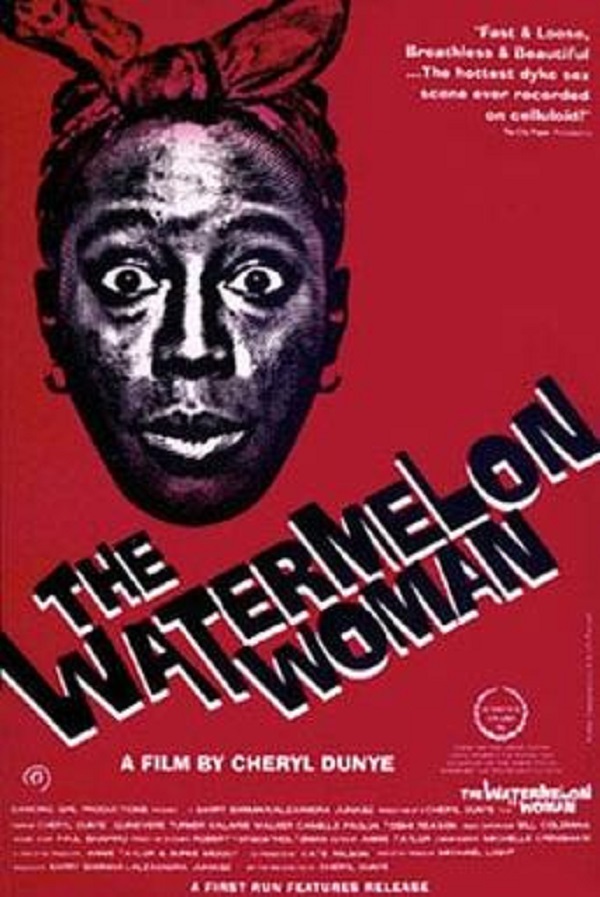

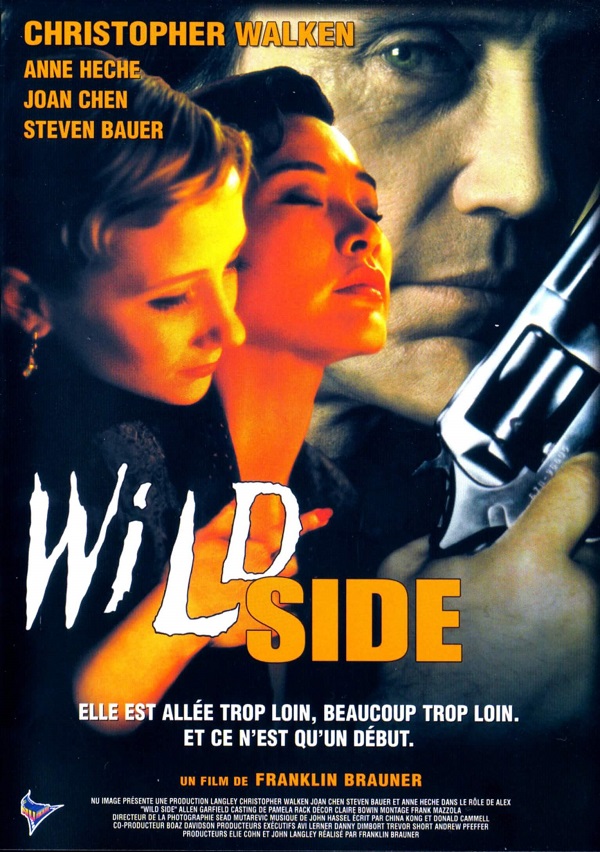

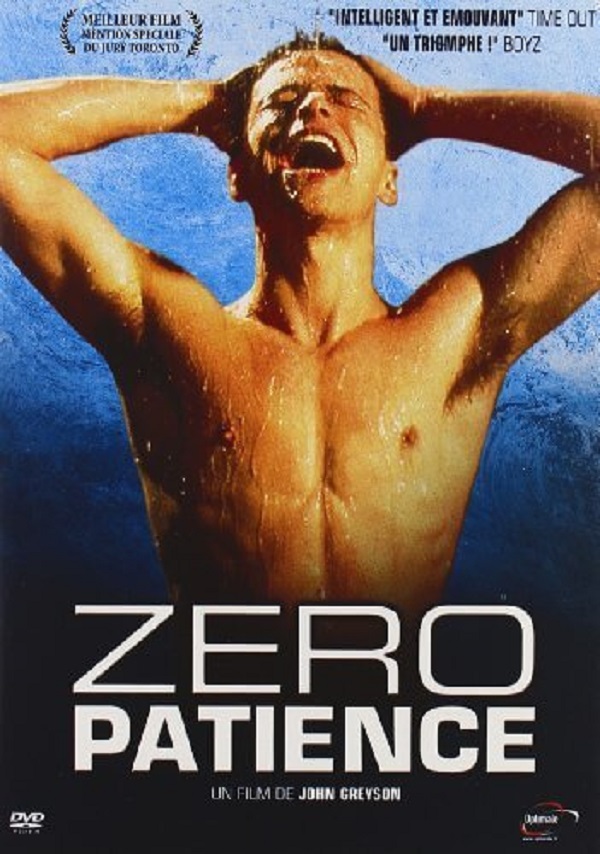

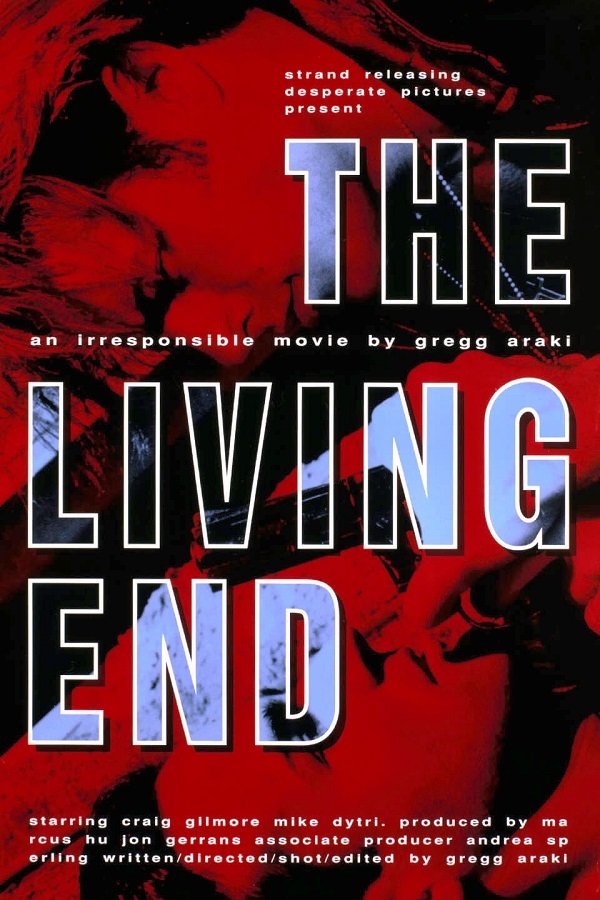

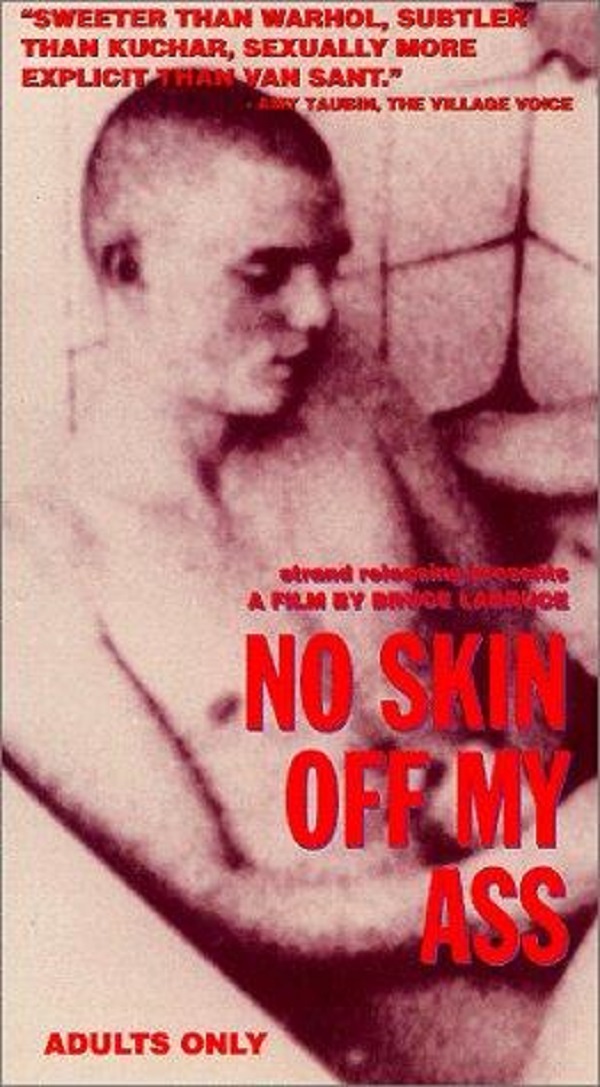

*The pics that accompany this article are posters of movies belonging by most accounts to the New Queer Cinema movement and they are offered here as recommendations!

References used:

B. Ruby Rich. “New Queer Cinema”: Sight & Sound, Volume 2, Issue 5 (September 1992)

B. Ruby Rich, New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut, Duke University Press, 2013.

Susan Hayward. "Queer cinema" in Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts (Third Edition). Routledge, 2006. p. 329-333.

David M. Halperin, How To Be Gay, Harvard University Press, 2014.

Michele Aaron, New Queer Cinema: A Critical Reader, Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Login

Login