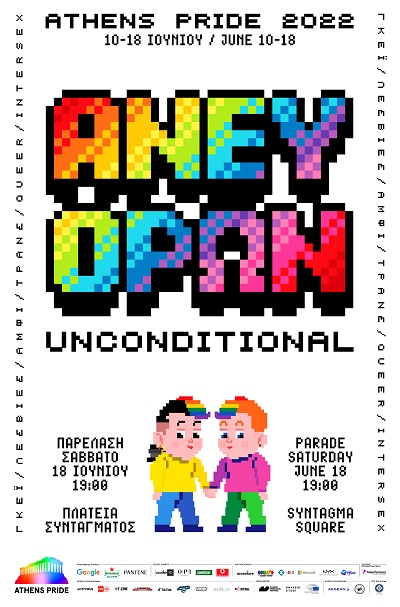

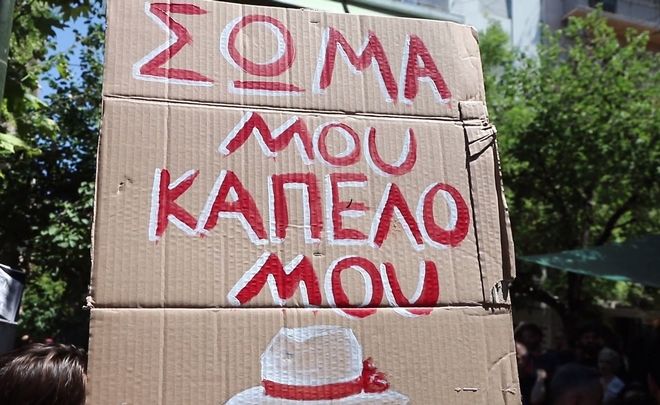

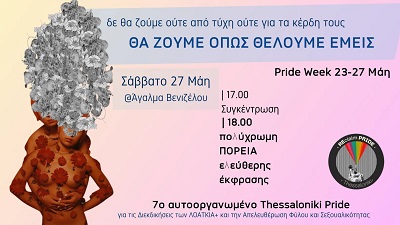

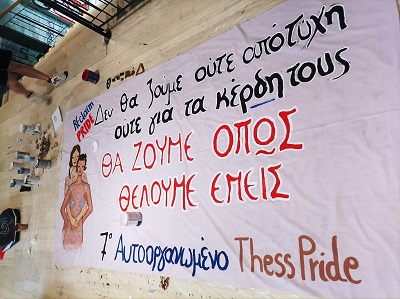

Happy Pride Month! As you already know, June is the LGBTIQA+ Pride Month observed each year in many places around the world! During this month, Pride Parades and festivals are organized along with panel discussions, networking meetings, campaigns, parties, photo exhibitions, movie nights, etc. The fact that June is selected as Pride Month is far from incidental. As we already discussed Pride Parade’s historical origins before over the course of Ecce Homo’s blog, it was on June 28, 1970, that the first Pride March took place in the streets of New York City following a police raid on the Stonewall Inn a year ago, a gay bar at 43 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, Manhattan. It was at this bar where a series of spontaneous demonstrations by members of the LGBTIQ+ community -among them many trans folks and queer people of color who usually get erased even from the stories they wrote themselves- took place. Protesting against the constant police harassment, a routine back in the 1960s, patrons of the Stonewall, other Village lesbian and gay bars, and neighborhood street people fought back when the police became violent. So, this is how the story goes! But what is at stake for Pride Month in 2023? Does the original spirit live one in today’s festivities? In what follows we will attempt at offering some preliminary insights on this matter taking the two biggest Pride Parades in Greece as our case study!

In the collective consciousness, the Stonewall Riots have been registered as the hallmark of the Gay Liberation Movement, a turning point in LGBTIQ+ history. These riots, also known as the Stonewall Uprising, have sparked the revolutionary political imaginary of millions of queer folks around the world ever since, given the global cultural influence of the USA on the rest of the world and the internationalization of LGBTIQ+ identities and of the movement itself. However, as rights and recognition have been gained over time, Pride itself has lost the radical and revolutionary character of a riot or a march and instead, it has turned into a multimillion-dollar industry of joyous festivities where, in many cases, the celebration of a hard-won and yet unfinished sexual liberation has displaced the serious political reflection. Take for example the way major fashion brands celebrate Pride Month with their rainbow-themed collections of products released every year. But let’s focus on the case of Greece, shall we? Here is a bit of the historical genealogy of Pride Parades in Greece and an initial mapping of their geographical distribution across the country.

Login

Login